1988: a Blast from the Past by Modern Means

written by Miranda Allegar - August 11, 2020

Would I ever accept a strange man’s request for help through my Instagram DM’s? Probably not. My direct messages are a space reserved for memes sent by close friends, quick conversations and well wishes to acquaintances I haven’t seen in years. I intentionally seek to maintain a private space for myself online, to the extent that that’s truly possible. This was the moment of willing suspension of disbelief that Denver Novelty Company’s 1988 required of me when I requested to follow their Instagram page for the project and turned my account on public to accept messages from any account.

To begin with, Denver Novelty Company itself is something of an enigma, self-described as creating “immersive and intermagical works intended to provoke feelings for a moment” and being formed in the 70’s to “sell kitsch novelty items to kids while simultaneously not existing at all.” The true origins are unclear. The web presence and websites are minimal. All other references appear to be some part of their other project, “146,” a web-based alternate reality game, or ARG, including a full back-story for the “company,” including concocted ads from alternate reality comic books. In this narrative, the Denver Novelty Company is portrayed as a roadside attraction, home to a mysterious creature.

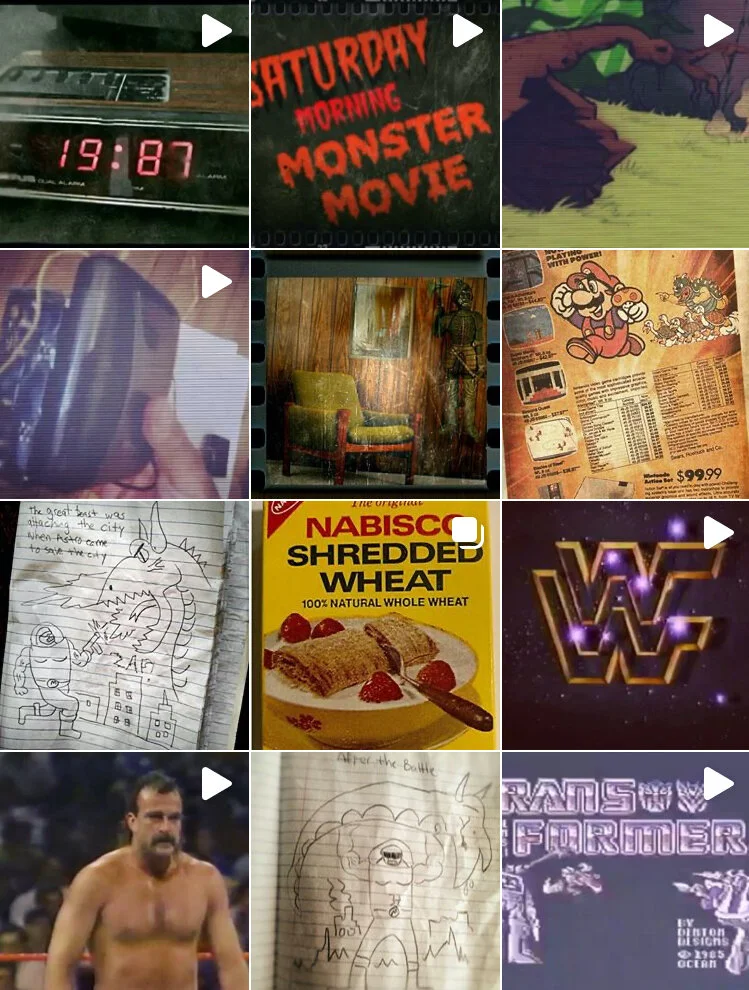

1988, their latest project, is a product of its moment, rife in nostalgia and centered in the collective experience of the pandemic. It’s conducted entirely through Instagram DMs and the project’s Instagram account, linked on the website with only a brief synopsis and a link inviting the player to “CLICK HERE TO JOIN!” What the experience will actually ask of its audience is unclear. Only the platform is revealed. I requested to follow the account (@saturdaymorning1988) and I waited. Some time later, my request was accepted. I clicked through the twenty or so posts on the Instagram page, chronologically walking through a Saturday morning in the life of a young boy in 1988 as he watches TV and plays video games. Then, I got a notification saying that I had received a new message from “Jackson.”

The young boy has grown up and been laid off due to the pandemic. Now, he asks for help in unraveling a mystery. Since his stepdad has died, he’s begun to receive enigmatic messages, starting with a tape with a strange URL he can’t access. The player is then asked to help out with these messages, embarking on a journey across the web, recorded 1-900 phone calls, a child’s hand-drawn mazes to complete, and plenty of questions about one’s own childhood experiences. Again, the game centers itself on nostalgia, full of references to Nintendo games and pop culture. I watched an 80’s-style video game play-through. I found myself in a brief conversation about Dance Dance Revolution.

I quickly lost myself in the experience. It felt engaging and realistic in a way I hadn’t yet experienced in virtual theater, mostly due to the fact that the experience was entirely perceived as one-on-one. Even with a sticky sweet center to the mystery I worked to solve (which readers owe to themselves to play through on their own) and some resulting moments of awareness I was playing a game, I found this latter aspect much less significant than I’d initially anticipated. In part, this was because the experience proceeds at your own pace more or less. While the account of “Jackson” responds pretty quickly generally, there’s no real rush to write back. There’s an organic nature to refreshing my Instagram app in search of a new notification and the next part of the puzzle, of pulling out a pad of sticky notes to jot down clues in a shaky video. Moreover, the personal questions about childhood memories and toys and insights into my own opinions about the mystery made me feel truly a part of the story. In the swath of virtual theater brought on by COVID-19, this common thread has been most compelling to me as companies battle against digital fatigue and shortened attention spans in their audiences. How can an audience be a part of the story rather than a passive observer as they may have been in a traditional theater?

Also, as I hinted, because the game unfolds through Instagram, it feels inherently personal—linked to one’s true self both as a person and in one’s online presence. I know I felt some vulnerability in playing through the game with my personal Instagram account and the details I share there. Further still, the game overlaps with real life through this platform. You might get a message, go do something else, and then come back to the next message or part, rather than sitting down for an experience in one extended performance. For me, the most jarring moments were the ones in which I got a message from a real-life friend while interacting with the game account, or vice versa.

In short, 1988 exists somewhere between the media of video game, short story, and participatory theater. The amount of effort behind the project is overwhelming, clear in the sheer quantity of associated materials disseminated to players– drawings, recordings, short videos created to appear like they’re shot by Jackson, the narrator, on his phone for you, ads, flyers, and more. The game’s massive dose of wistful longing for a childhood gone past is one born for the time of the pandemic, woven with threads of fear, anxiety, and personal growth, all too familiar right now. Even larger issues loom in the shadows of the game: the death of loved ones, financial instability. I found 1988 eerily reminiscent of the way so many of us are spending time in childhood homes and bedrooms right now, rediscovering the person we were when we last lived here and reconciling that self with the present. Much like Jackson, the past few months have forced many of us to use the past as a benchmark for our current selves as we slow down in the way that the pandemic has necessitated.

Ultimately, there was something almost unsettling about the whole experience. The blend of nostalgia, suspended reality, lack of web presence for the project, and direct immersive style lives squarely in the uncanny valley that the Internet provides so well—not quite human or organic, but not entirely artificial either. 1988 creates a world not unlike the endless loop of a day many of us have lived for the past five months, one in which it’s hard to tell where reality starts and ends.

Experience “1988” by Brett Hughes and Denver Novelty Company here.