Shelley Butler

SHELLEY BUTLER: So I'm a stage director with a focus on new plays, but also classics and musicals as well. When the pandemic hit, obviously all of my work shut down as it did for so many of us; a whole season and beyond put on hold or canceled. I am married to another director, so both our seasons melted away. When it struck, he was in rehearsals in Las Vegas and my ten-year-old and I had just joined him for spring break. We flew on Friday the 13th of March and, three days later, the whole strip shut down.

So we thought, well, we'll rent an RV and go see the Grand Canyon and come back in a week. Of course, we all know what happened. So we decided to just drive east, drive cross-country. And we spent some of that drive thinking about “what do we value in a theater experience, and what can you make when there's no live gathering?”

We landed in South Carolina at the same time my husband took part in the Orchard Project Liveness Lab. There were a whole bunch of zoom rooms that were devoted to AR [augmented reality] and VR [virtual reality] but he went in the one room devoted to plays for text, email, and mail. And the lab was huge but there were maybe three people in this room and they started talking about the live quality of epistolary exchange. One of the people in that room was a writer named Natalie Ann Valentine, who is an amazing multi-disciplinary artist—a burlesque artist as well. And she was talking about the power of mail and simple creative acts like mailing someone seeds they could then plant. My husband got sparked by that encounter and we started imagining whole stories told this way.

We decided to see if we could create something that would be an immersive experience in the form of interactive plays-by-mail. We got excited about the sensory and tactile potential of the artform—you can send something scented, you can send ingredients for cooking- being in a live theater space is a multi-sensory experience and letters also offer those kinds of opportunities to awaken all the senses.

We seized on the importance of the give-and-take interaction with the audience. In the live experience the actor's performance is impacted by a silent house, by a raucous house. And we were both doing some Zoom—and people are innovating within that form brilliantly—but it's generally a cold experience. Even when we're talking to each other in real-time on zoom it lacks the electricity of an in-person exchange. Rarely is the performance impacted or shifted by the audience. Whereas a letter exchange is, by nature, designed for and thrives on that powerful give-and-take between performance and audience response.

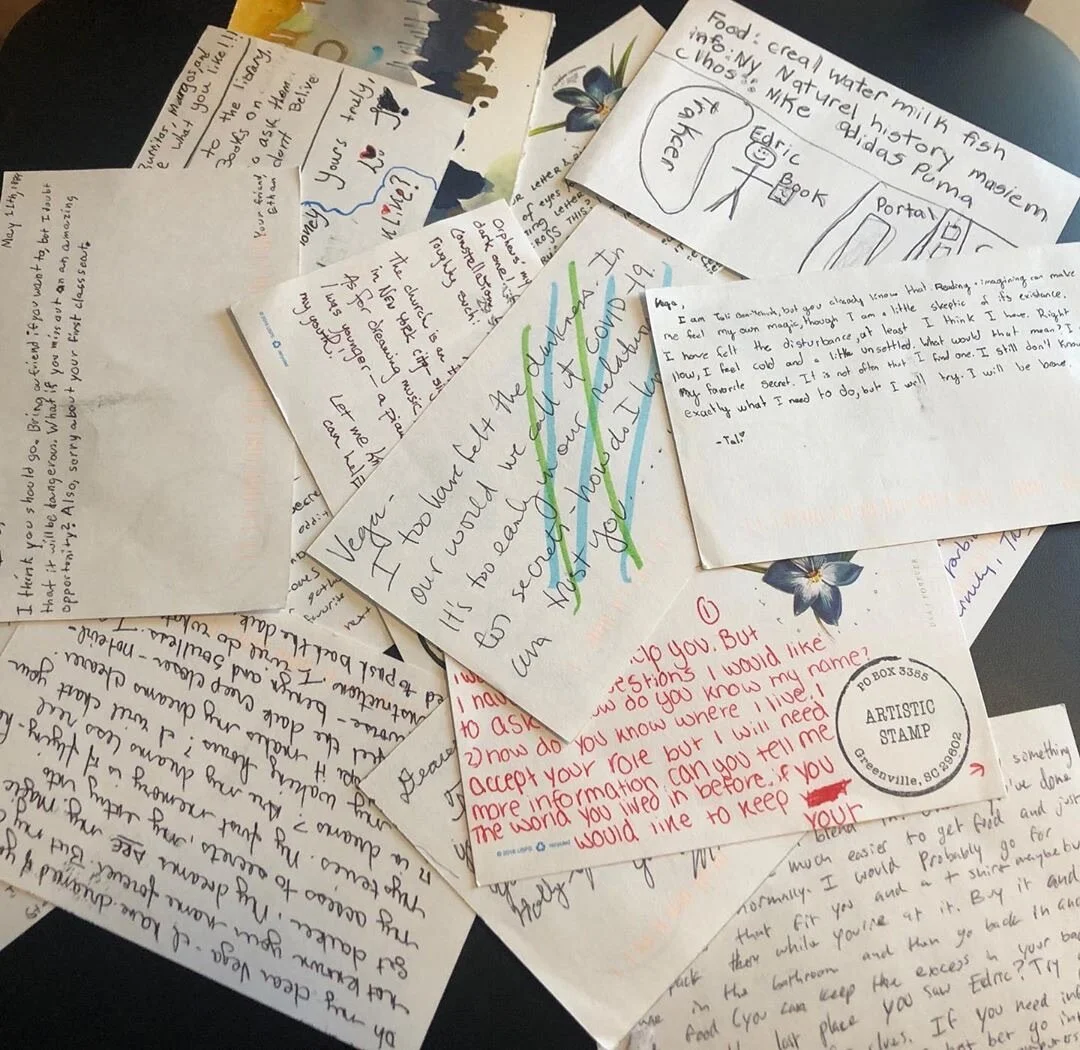

MIRANDA ALLEGAR: I was so fascinated reading through the samples that you sent over. One thing that really struck me was the difference between reading the drafted versions in a word processing document and then how it really comes to life when it's handwritten and marked up and annotated. And I think that that's so beautiful, the way that the handwriting becomes this extra level of intimacy and interactivity.

SB: It's really true. It has been wild to compare the responses of audience members to different actors: they are partly reacting to how the actors improv, but also to their handwriting. It's a different voice—some read warmer or sharper-- but in all instances a personality comes through. You can also convey so many things about circumstances and what's happening in that moment through style. And we love the marginalia and things like notes on the envelopes. The Otherwise series, which is Natalie Ann Valentine’s Wiccan adventure, is the most visual with evocative drawings and doodling. And I would say it's a little bit of a mood piece. Story is not the leading Aristotelian element. And it often evokes a similar response from its audience. We're getting back beautifully drawn pieces of art and an energy that plays off what they received.

MA: I noticed that even in more story-driven pieces, syntax would change to match the letter that they had received or the perceived time period.

SB: Great observation, yes! Audiences frequently slip seamlessly into the language and feel of the world set forth by the playwright and actor.

MA: How did you set about building a team for this project?

SB: First we reached out to playwrights we hoped to commission. We were looking for a diverse and inclusive cohort of artists with a wide range of stories and styles. We set out to learn what could be done with the form: would a young audience piece work this way? Would romance or nostalgic comedy play well? And in seeking these primary collaborators we were looking for folks equally curious about exploring the form.

And you might've noticed we have a lot of musical theater writers. And I think that's because the form demands collaboration. If you are a writer who says, "Here's my story," it doesn't work. You have to want the audience to participate. You have to want them as a collaborator. You have to let the actors in too. And musical theater writers are generally accustomed to working with multiple collaborators and seemed to welcome the adventure.

Once we had our stories, casting was an unusual ask. We first thought, “Oh, maybe it's just people with beautiful handwriting,” but the actor part has turned out to be the key.

So yes, they are writing it out by hand and it has to be legible (that’s part of the audition) but equally important is making the audience feel seen. The actors’ have to actively listen and then improv back in the voice of the character—that’s the thing that makes it work. The playwright pens the bulk of the story, but the actor makes the experience bespoke by actively listening and ensuring the audience’s responses get woven into the story. And when they do that, it's really theater for one. No two experiences are the same because it is tailored for you.

MA: What has it meant to direct this piece?

SB: It's a great question. So of course there are elements that transfer more directly. The work with the writers resembles the development and dramaturgy that West [Hyler; co-artistic director of Artistic Stamp and Shelley Butler’s spouse] and I would do on any new play. And we’re working with actors to ensure they are “in character” with their improv.

But the bigger question or discovery for me has been the joy of centering the audience. That's the biggest takeaway for me from this whole project. How do they [the audience] enter into it and factor into the whole journey?

I assisted Bill Rauch twenty years ago and at intermission, he would go into the lobby and poll the audience for their response to things. That really freaked me out, partly because I was a bit of an introvert. And also, I think I had some maybe egoist idea about creating art. And why would you ask them? And, you know, I was twenty-one. But Bill said to me, "Shelley, who are we making this theater for?"

That stuck with me and doing this piece brought it rushing back, because we know how our audience feels in a way that I never have, even with the most successful theater pieces that I've worked on. With this form we know if a particular letter is working because the audience tells us, both by how they respond and by when they don't respond. Some letters elicit lengthy passionate responses and others get simpler, shorter responses.

And a big part of it is setting up the rules of the game. And that feels like direction, in collaboration with playwright, of course. Because if the audience doesn't know how they're cast or how to play, it's not as fun for them and they won’t feel invited in.

MA: I think that audience engagement is what's been so exciting to me about theater this year in particular. Bridging that gap, coming into an audience member's home rather than having them come to a theater; it's such a transformation of what theater can be. And also this unsilo-ing of different types of collaboration, very much what you're describing between the playwrights, the actors, the audience, and yourself as a director.

SB: And you also hit on an important element of it, which is access, because you can get a letter whatever your mobility or no matter your comfort in a social setting. And you can do it without good broadband too. In the future, we’d love to do dual language versions to be able to reach a broader audience. Economically, I wish I could break down that barrier. We're just not there yet. We haven't figured out a way to make it less labor intensive though perhaps grant opportunities will be the key. I am super proud of the fact that we have been able to commission playwrights and pay actors. It's not a large amount, but West just did the math and we have paid out over $15,000 to actors and playwrights, which, for a pair of freelance directors working out of their living room, feels like a huge accomplishment in a time where it's so hard to generate funds for the arts.

MA: Touching on your point about accessibility, that's something I've been thinking about – I can imagine what a break it is to get to experience this story in an analog form and step away from the computer but still have this artistic experience as an audience member. And the timespan that this takes, rather than being this concentrated set period of time where you're looking at your computer screen or doing an activity or watching a play. It unfolds with this immense swath of time necessitated by the written form. How do you think that has impacted the piece?

SB: I think that's why it works. You get it in chunks so it builds tension and suspense for the audience member like long form narrative serials. You have an immediate visceral reaction, but then you can ponder your response and wait to see how it’s received. One of the things I love the most about this is the ability to create empathy. That's what I’m always trying to do with my work on stage. And I think sometimes it is successful and sometimes it isn't. But in this form you up the chances of empathy because you’re cast in proximity to the main character—so, you're not reading about Ida B. Wells historically in the past or from a distance. You are her best friend from Holly Springs. So you go through all those experiences with her and you feel like you are a part of that piece of history in a very intimate way. And I think that having that happen over time increases that relationship. As you wait to find out what happened to her, your friend, you imagine a hundred different outcomes and that passage of time causes her to be frequently on your mind, all of which is helpful to empathetic relationships.

MA: What has been most surprising to you about this process?

SB: I went into it thinking we'd have to work really hard to get them to respond. In every letter you get a pre-stamped postcard, so that it's easy. If you're busy, you can just jot whatever you have to say on the back and put it in the mail. And I was really trying to push the writers to engineer it to have a very clear question, a directive for the audience to answer, so that we would get a response. I didn't need to do that. People are hungry for connection. People were eager to respond. The biggest surprise has been how well it works.

I was also surprised by how personal it became for a lot of audience members. We talked about the centralizing of the audience and the one-on-one experience. And, of course, in live theater, I really treasure the collective heartbeat that we talk about, but there's something special about not having that pressure, that you can read that letter and your response can be uniquely your own and that can then impact the story.

MA:. One of the other things that I have been thinking about was both the intimacy and the chance for socialization amidst this period of isolation, feeling like you're building a relationship with the character that you're writing to. How did that play into your shaping of this process, thinking about intimacy and connection within the pandemic in particular?

SB: I will say we made an upfront decision not to create any stories about quarantine or about the pandemic. Reaching into people's homes, we wanted to give them an escape or an adventure or something different than the life that we're all living every day in quarantine but also to provide them an artistic outlet and a kind of company.

We also have some school groups on our young audience pieces. One of our schools remained virtual for the whole letter arc so giving them the opportunity to collaborate and go on an adventure together felt powerful in the pandemic.

We felt a great responsibility to engender hope, to share humor, to provide adventure and to try and give our audience something to look forward to and make them excited to check their mailbox. We’ve had audience members say, “I really didn't even go to the grocery store. I ordered everything and I wasn't having any contact.” And when the letter would come they’d get a lift from that connection.

MA: I have started so many letter exchanges with my own friends this year after being apart for so long. It feels like it's the right pace for life in quarantine. I think we both end up looking forward to this tangible, exciting thing, if for nothing else to be excited when you know that the postman has come by for the day and to get to check the box and see maybe today. And, if not today, maybe the next day. Maintain some sense of time moving forward.

SB: I love that. Do you all share any letter art?

MA: I've got doodles, pressed flowers, stickers, and I love that. I've always been a big letter writer. But I think having this moment in time in particular—it's been just the right pace to keep up connections with the people I care about. And so it's very exciting to see that intersect with theater and storytelling.

SB: I love what you said about the pace of it because you really hit something I don't even know that I thought about. That pace is part of why it fits in so well into the world in this moment.

MA: How do you think that working through this media and this format has changed your definition of theater?

SB: It made me ask what do we value in the theater experience? It's making me ask, what do I want out of theater? I’m deeply uninterested by the reductive “is it theater” critique that has been leveled at almost all pandemic art and I think just expanding the definition and the directions in which we explore art in general is incredibly exciting. Theater has been exclusionary in so many ways, about who gets to make it, who views it, how you access it. And that actually feels antithetical to this thing we all got into. Certainly the essential reckoning that's happened with “We See You White American Theater” has made crystal clear that we have failed in terms of theater being inclusive, of inviting everyone and incorporating everybody. And I feel like we should be experimenting and expanding our thinking in many directions about what art can be, a bolder and broader imagining of theater should be welcomed and encouraged.

MA: What has continuing to make theater this year meant to you? Why has it felt important to keep creating?

SB: For better or worse I sort of don't know how to not make. And so creating this company with West has really sustained my spirits throughout the pause, to be able to put something positive into the world, and also selfishly to have an outlet for all of the things that I'm holding onto. Frankly we ourselves were as hungry for connection as our audience.

MA: Do you think Artistic Stamp will continue after the pandemic?

SB: Yes, but it will continue to morph and change form. We’re currently preparing to launch multiple education models: we’re piloting one program where the letter series is interwoven with a specific school curriculum, we are in development for another hybrid model where a letter play will include a related live performance component, AND we’re about to launch a version in which students will actually be the actors—corresponding with their own communities. We will have one final public season go on sale in April and run through this summer that will stay true to the original form we’ve pioneered, but then it will be time to explore in a new direction.

For more information on Artistic Stamp and Shelley Butler, visit their website here.