virtual Puppeteering

written by Katharine Matthias - August 5, 2020

Puppetry and live, in-person theater often necessitate a mimetic imagination; that is, objects in both puppetry and live, in-person theater represent something other than what they are. Puppet theater translates materiality to the otherwise immaterial, virtual stage.

Certain theaters have been exploring how puppets function on the cyber-stage during the pandemic, including Great Small Works’ “International Toy Theater Festival” and the DP TV (Dixon Place TV) program run through the Dixon Place theater. Great Small Works is a New York-based performance collective that has produced several days of a virtual international toy theater festival over the course of the pandemic. The work, which is still accessible on their Facebook page, centers around Toy Theater. In their recent workshop with AQM - Association québécoise des marionnettistes, John Bell, one of the co-Artistic Directors of Great Small Works, notes the five rules of Toy Theater, stating that Toy Theater must have a proscenium arch, must exist in a miniature form, be made from paper, be two-dimensional, and it should be accessible to everyone. Bell notes in the workshop that Great Small Works began to explore the old puppetry form of Toy Theater when the United States started the Iraq War. The group took propaganda for the war from newspapers and made their own version of the news in Toy Theater style, calling upon the tradition of the “Living Newspaper” theatrical form. Trudi Cohen, one of the other co-Artistic Directors of Great Small Works, notes later in the same workshop that Toy Theater translated onto the screen with surprising efficacy during the International Toy Theater Festival. She notes that the screen and the 19th Century Proscenium in Toy Theater share an intimacy that perhaps allows Toy Theater to translate so well onto the digital stage.

Like the International Toy Theater Festival, the DP TV program also invites several puppet artists to create work, which Dixon Place displays for free on their website. In Shayna Strype’s piece “Hearty Fluff,” Strype utilizes her own voice to make many sound effects for the video, which perhaps maintains some of the directness and imaginative quality of live theater. The materiality of Strype’s hand-crafted puppets in the virtual theater lends an organic quality to the puppets on the otherwise inorganic stage. Both the International Toy Theater Festival and the DP TV program provide accessibility to a wide range of puppet styles and puppet shows, and it invites the audience to engage directly with the puppet work on the screen.

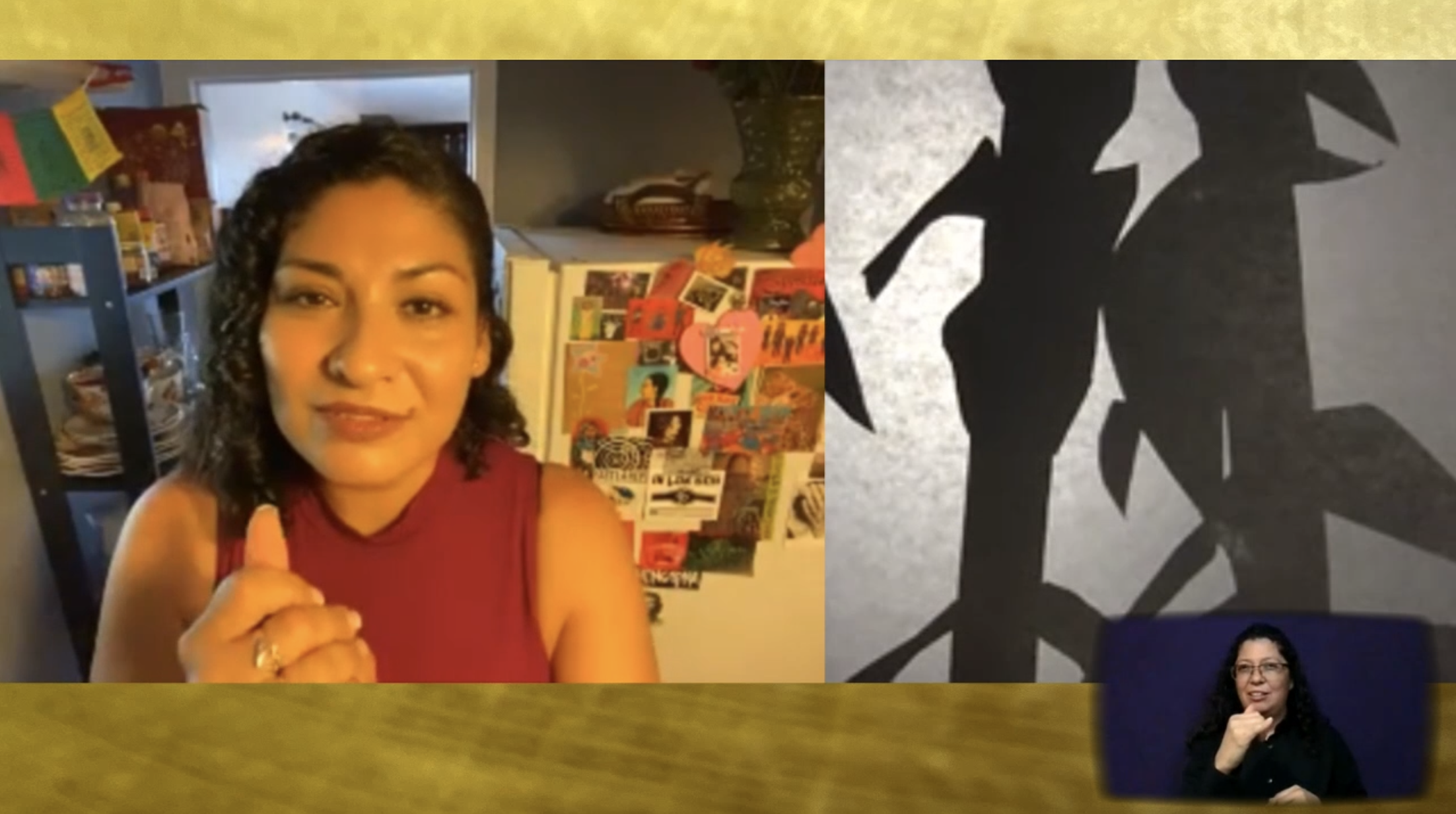

Perhaps the striking quality of handmade puppets is their organic quality on the otherwise inorganic stage. In Virginia Grise’s a farm for meme, director Elena Araoz interweaves Marlene Beltran’s performance of the show’s non-linear monologue about South Central Farm with puppetry that blossoms on screen, depicting the organic landscape of the farm.

In the rehearsal process, Elena asked the puppetry performers -- BT Hayes, Katharine Matthias, and Minjae Kim -- to explore what nature growing looks like on the virtual stage. Like the Toy Theater rules described by John Bell, the puppetry in a farm for meme relies on cardboard stages, shadows puppets, and paper leaves to create the material, organic quality on the inorganic cyber-stage.

Handmade puppetry, however, does not represent the only explorations into puppetry during this pandemic; Artificial Reality (AR) applications perhaps are an example of another kind of puppetry, albeit a virtual kind.

In posthumanist scholar N. Katherine Hayles’ “How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics,” she notes that “embodiment has been systematically downplayed or erased in the cybernetic construction of the posthuman” (4). In her book, she argues that we live as “embodied creatures living within and through embodied worlds and embodied words” (24). With N. Katherine Hayles’ framework of embodied virtuality, artificial reality applications and programs could be understood as a kind of virtual puppetry that remains just as embodied as hand-crafted, material puppetry.

Several different applications can also be framed as digital puppetry on the virtual stage. For instance, in the application “Acute Art,” the VR application has been designed as a gallery for interactive art and defined as “a gallery without walls.” The application functions as its own kind of embodied experience that requires the viewer to place and interact with virtual objects through their phone and expands the boundaries of where interaction with art can take place. While the application was created as a way to interact with famous artists' work rather than create a space where one could publish their own AR work, it offers the live virtual theater-maker the chance to expand and perhaps create theater pieces that are completely on one's phone and mediated through an AR experience. This reimagining of where art can occur and how it can be made pertains to both the traditional Toy Theater -- as mentioned above -- as well as the AR experience of Acute Art. The artwork in the app allows the viewer to interact with and ultimately puppet and position the art around them through their phone screen.

Similarly, Spark AR is another artificial reality application that is run through Facebook and allows anyone to create their own augmented reality effects for either Facebook or Instagram. Through Spark AR, the artificial reality maker perhaps becomes their own puppeteer; however, instead of the stage being the formal proscenium for the puppeteer, the new proscenium is rather one’s phone or the computer. Ultimately, puppetry -- both hand and artificially made -- offers and explores where the proscenium now lies in virtual live performance.